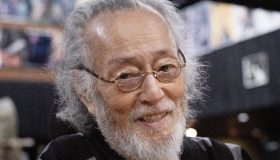

When the news broke that Tatsuya Nakadai, the towering icon of Japanese cinema, had passed away at the age of ninety-two, an era quietly ended. For over seven decades, Nakadai embodied the soul of Japan’s post-war screen — a man whose very presence could silence a room. He was not merely an actor; he was a force of nature, sculpted from steel and poetry, with a voice that could freeze your blood and a gaze that could pierce through time itself.

Today, as the world whispers its final rest in peace, we look back on the life, voice, and legacy of one of the greatest performers to ever walk in front of a camera.

A Voice Forged in Fire: The Ice-Cold Authority of Tatsuya Nakadai

Nakadai’s voice was unlike any other — low, deliberate, masculine yet strangely melodic. It was the kind of tone that could command armies or whisper confessions of guilt in the dead of night. Critics often described it as “ice-cold,” not because it lacked emotion, but because it restrained emotion like a blade sheathed in silk. When he spoke, every syllable carried weight. Each pause was purposeful, like a warrior calculating his next strike.

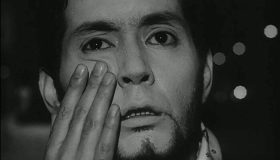

In the cinematic universe of the 1950s and 60s, when Japanese film was dominated by fiery deliveries and theatrical flourishes, Nakadai arrived as a storm of quiet. He could intimidate without raising his voice; he could grieve without shedding a tear. His performances taught generations of actors the art of stillness — the power of doing less, and meaning more.

Watch him in Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962), and you’ll witness this mastery. As Hanshirō Tsugumo, a ronin seeking vengeance in a corrupt samurai house, Nakadai doesn’t scream his rage — he speaks it softly, each line vibrating with suppressed fury. His voice in those scenes is almost hypnotic: calm, precise, terrifying in its control. When he finally unleashes his truth, it feels like the calm of winter cracking open to reveal molten fire beneath.

Even decades later, in Kurosawa’s Ran (1985), Nakadai’s vocal authority remained unparalleled. As the aging warlord Hidetora, descending into madness, his lines carry a trembling grandeur — like the echo of an emperor whose world is collapsing but whose voice refuses to surrender dignity. It wasn’t just acting; it was oration sculpted into art.

Nakadai once said in an interview, “Silence is not emptiness. It is tension.” That philosophy defined his style. He treated dialogue as music: rhythm, pitch, silence, and power intertwined. His voice was never just a sound — it was a weapon, honed over a lifetime of discipline.

The Making of a Giant: From Ordinary Man to Myth

Tatsuya Nakadai was born in Tokyo in 1932, during a time when Japan’s identity was shifting under the weight of modernity and war. He grew up during the dark years of World War II, witnessing the devastation of Tokyo’s bombings. That experience would later seep into his performances — the quiet pain, the internal struggle, the melancholy that would define many of his roles.

He wasn’t born into privilege or the arts. In fact, his entry into acting was almost accidental. While working in a Ginza department store, Nakadai was discovered by a casting assistant who noticed his striking face and disciplined posture. He was soon introduced to the world of film, and his destiny began to take shape.

He trained rigorously in theatre before stepping into cinema. This stage background became the skeleton of his screen persona — every gesture, every turn of the head, calculated yet alive. While most actors of his generation learned from studio systems, Nakadai carved his own path, refusing long-term contracts and working independently. This gave him creative freedom, allowing him to collaborate with the greatest directors of Japanese cinema — Masaki Kobayashi, Akira Kurosawa, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Mikio Naruse, and many others.

His partnership with Kobayashi defined the early years: The Human Condition trilogy, Harakiri, and Samurai Rebellion. With Kurosawa came Yojimbo, Kagemusha, and Ran — films that would immortalize both men in world cinema. And yet, Nakadai’s genius was that he could exist equally well in small arthouse films, stage productions, and even animated features late in life.

By the time the West “discovered” Japanese cinema through Kurosawa’s lens, Nakadai had already become a living legend at home. But fame never interested him; what drove him was craft. In countless interviews, he spoke about “disappearing into a role,” about the need for humility before art. “An actor,” he said, “must be invisible, yet unforgettable.”

The Human Condition: The Birth of a Legend

If one were to choose a single performance that announced Nakadai to the world, it would be The Human Condition (1959–1961), Kobayashi’s epic trilogy about one man’s moral survival in wartime Japan. Playing Kaji, a pacifist thrown into the hell of war and forced to confront the collapse of his ideals, Nakadai carried the entire nine-hour saga on his shoulders.

What he accomplished in that role was staggering. He aged, suffered, and transformed before the audience’s eyes — not through makeup or cinematic tricks, but through internal metamorphosis. His delivery oscillated between empathy and despair, idealism and rage. In one unforgettable scene, Kaji speaks to a group of war prisoners about humanity, his voice trembling with both compassion and hopelessness. That voice — firm but breaking — became the moral conscience of post-war Japan.

Critics around the world later compared The Human Condition to War and Peace, calling Nakadai’s Kaji “one of the most complete performances in film history.” For him, it was a turning point. “Kaji taught me,” Nakadai once said, “that acting is suffering — not pretending to suffer.”

The Sword and the Silence: Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion

Nakadai’s collaboration with Masaki Kobayashi continued into Harakiri (1962), often considered one of the greatest samurai films ever made. Unlike the glorified warriors of traditional cinema, Harakiri stripped the myth bare. It was an indictment of hypocrisy and blind loyalty — and Nakadai was its vessel.

As Tsugumo Hanshirō, a masterless samurai seeking vengeance for the cruel death of his son-in-law, Nakadai played the role with chilling restraint. The early scenes show him as a calm, respectful visitor, politely requesting permission to commit seppuku in a noble house. But as the story unfolds, his calm becomes a blade sharper than any sword. His line delivery in this film remains a masterclass: steady, slow, cutting through lies with a rhythm that feels like poetry.

When Hanshirō recounts his story to the arrogant officials, Nakadai’s voice turns into thunder wrapped in ice. There is no shouting, no theatrics — just gravity. Every pause hits like the strike of a drum. His closing monologue — about the emptiness of “honor” in a corrupt system — remains one of the most powerful speeches ever spoken in Japanese cinema.

In Samurai Rebellion (1967), also directed by Kobayashi, Nakadai shared the screen with the great Toshiro Mifune. The two men, representing different generations of acting philosophy, clashed and harmonized perfectly. Mifune’s fire met Nakadai’s ice — and together, they created cinematic electricity. Where Mifune roared, Nakadai whispered; where Mifune charged, Nakadai calculated. Their final duel is still studied today for its emotional complexity — a confrontation between pride and principle, chaos and calm.

Kurosawa’s Shadow: Yojimbo, Kagemusha, and Ran

Although Nakadai never became Kurosawa’s regular leading man like Mifune, their collaborations produced unforgettable results. In Yojimbo (1961), he played Unosuke, the pistol-wielding antagonist — the mirror opposite of Mifune’s wandering ronin. Nakadai’s smirking villain, exuding both charm and cruelty, gave the film its edge. His cool demeanor and modern swagger hinted at Japan’s coming transformation, making him one of Kurosawa’s most memorable antagonists.

But it was Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985) that cemented Nakadai as Kurosawa’s heir to tragic grandeur. In Kagemusha, he delivered a dual performance — both the powerful warlord Takeda Shingen and the lowly thief who becomes his double. The transformation was breathtaking. Through voice alone, Nakadai distinguished the two men: Shingen’s tone deep and commanding, the double’s hesitant and insecure. By the film’s end, when the impostor begins to believe he truly is the lord, Nakadai’s voice grows stronger — until his illusion is shattered by death. It’s one of the most haunting sound arcs in cinema.

Then came Ran, Kurosawa’s epic adaptation of King Lear, where Nakadai played Hidetora Ichimonji, an aging warlord descending into madness after dividing his kingdom among his sons. Here, Nakadai achieved something beyond acting — a transcendence. Covered in white makeup, his voice cracked with age and grief but never lost authority. His cries of despair in the ruined castle, his hollow laughter in the storm, became images burned into the collective memory of world cinema.

In Ran, Nakadai embodied the collapse of order, of patriarchy, of the self. His performance was Shakespearean in scale, yet deeply Japanese in soul. Few actors in history have captured the majesty of decay with such icy, regal despair.

The Philosopher Actor: Beyond the Screen

What made Nakadai different from his contemporaries wasn’t just his skill but his philosophy of acting. He believed that the craft was spiritual — a way of confronting truth. “Every role,” he once said, “is a mirror. If you look long enough, you’ll see yourself — and sometimes, that’s terrifying.”

He founded Mumeijuku, a theatre school in 1975, dedicated to training actors in both classical and experimental forms. Unlike most celebrity academies, Mumeijuku was strict and ascetic. Students were expected to meditate, to study body language, and to understand silence as deeply as dialogue. For Nakadai, the voice was not just produced from the throat — it was summoned from the soul.

His students recall his lessons vividly: “Speak as if your breath were your heartbeat. When you stop believing in your own breath, the audience stops believing in your life.” That philosophy shaped generations of Japanese performers who followed him.

Even in his later years, Nakadai continued acting — in theatre, television, and even voice roles in animation. He lent his voice to The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), proving that even at eighty, his tone retained that timeless authority: the sound of experience distilled into every syllable.

Quotes That Echo Through Time

Nakadai’s filmography is filled with unforgettable lines, each delivered with the precision and gravity that became his signature. Here are some of his most memorable quotes, translated from Japanese, capturing both his ice-cold delivery and his philosophical depth.

From Harakiri (1962)

“Honor without mercy is hollow. A blade polished only for pride cuts no deeper than the wind.”

“I do not fear death. I fear a life where meaning is taken from men and replaced with ceremony.”

“Silence is sharper than any sword. It cuts the lies cleanly.”

From The Human Condition (1959–61)

“To survive is not to live. To live is to remember what makes us human.”

“They say the strong rule the weak. But in war, everyone kneels before hunger.”

From Ran (1985)

“The storm outside is nothing compared to the storm within.”

“When gods abandon us, we create new gods — and call them sons.”

“A king who divides his kingdom divides his soul.”

From Kagemusha (1980)

“A shadow can rule an empire, but it can never feel the sun.”

“I was a thief once, then a king’s ghost. Both were lies — but one felt real.”

These quotes endure not only for their poetry but because of how Nakadai delivered them — with the weight of silence before and after, as if each sentence were carved into stone.

A Filmography Etched in Eternity

Nakadai appeared in more than 160 films, covering every imaginable genre: historical epics, psychological dramas, noir thrillers, and quiet domestic tragedies. His versatility defied categorization. Below are some of the defining works of his long, astonishing career:

-

The Human Condition Trilogy (1959–61) – The role of Kaji, his breakthrough, remains a cornerstone of world cinema.

-

Harakiri (1962) – A masterpiece of moral fury; Nakadai’s quiet vengeance became legendary.

-

Yojimbo (1961) – As the pistol-wielding villain Unosuke, he challenged Mifune’s archetype with icy modernity.

-

Samurai Rebellion (1967) – A poignant exploration of loyalty and love in feudal Japan.

-

The Sword of Doom (1966) – As Ryunosuke Tsuchigane, a killer consumed by nihilism, Nakadai personified madness itself.

-

Kagemusha (1980) – The duality of identity — the thief and the lord, both haunted by illusion.

-

Ran (1985) – His magnum opus; the voice of apocalypse given human form.

-

Goyokin (1969) – A reflective samurai drama where morality clashes with duty.

-

The Insect Woman (1963) and The Face of Another (1966) – Collaborations with Hiroshi Teshigahara exploring identity and alienation.

-

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960) – A tender, modern drama showing his range beyond samurai films.

-

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) – His last major role, lending his legendary voice to an animated masterpiece.

Each film is a chapter in the evolution of Japanese acting — a study in precision, restraint, and emotional truth. Nakadai could inhabit heroes and villains, peasants and princes, with equal conviction. What united them all was the moral gravity he brought — the sense that every word mattered, every silence meant something.

The Man Behind the Mask

Off-screen, Nakadai was remarkably humble. Colleagues described him as gentle, disciplined, and endlessly curious. He practiced calligraphy, read philosophy, and believed deeply in the Japanese concept of ikigai — the reason for being. Acting, for him, was not a profession; it was a calling.

He often said that his voice came from “breathing through memory.” He believed that the body carries the echoes of every experience — childhood fear, first love, grief, triumph — and that true acting means unlocking those echoes. “When I deliver a line,” he explained, “I am speaking for every man who cannot.”

His on-set reputation was one of perfectionism. He arrived early, memorized not only his own lines but everyone else’s, and treated every crew member with equal respect. Directors loved him because he never asked for special treatment. “He worked like a monk,” said one cinematographer. “Even when playing a king.”

The Passing of a Legend

When Tatsuya Nakadai died peacefully in November 2025, the world paused. Japan’s film industry, critics, and audiences alike mourned the loss of its last living bridge between post-war realism and classical grandeur. For decades, Nakadai had stood as a symbol of dignity — a reminder of when cinema was art, not spectacle.

Tributes poured in from actors and directors across generations. Many called him “the soul of Japanese cinema.” Younger stars cited him as their blueprint: a man who proved that masculinity could coexist with vulnerability, that power could be quiet, that authority could be born from empathy.

In his final years, Nakadai spoke often about mortality. “An actor dies twice,” he said. “Once when his role ends, and again when he can no longer take the stage. Both deaths are beautiful if they serve the story.”

Now, his story is complete — and what a story it is.

Legacy: The Eternal Echo of an Ice-Cold Voice

The legacy of Tatsuya Nakadai cannot be summarized merely in awards or film counts. His true inheritance is emotional: the way his characters linger long after the credits fade. His voice, that deep manly resonance, has become a symbol of timeless masculinity — not loud or boastful, but grounded, intelligent, and unyielding.

In an age where performances are often inflated with noise and spectacle, Nakadai’s restraint feels revolutionary. He taught us that strength is quiet, that emotion is most powerful when held in tension, and that an actor’s greatest weapon is truth.

His films will continue to educate not only performers but audiences — showing that art, at its highest form, transcends language, culture, and time.

As the credits roll on his life, one imagines Nakadai standing in a quiet field, samurai armor gleaming, eyes steady on the horizon, wind brushing through his gray hair. The voice that once echoed across cinematic history now whispers into eternity:

“To live with dignity… is the hardest role of all.”